Designing a Social Media ProtocolSTOA (Standards for Transparent Online Agency) is a social media protocol designed to make interpretive decisions in digital systems visible, inspectable, and user-governed.

Overview

Role: Creator & Product Architect — Interaction Systems, Emerging Paradigms, Technical Design

Organization: Independent Design Science Project

Industry: Large-Scale Social Platforms · Algorithmic Systems · Platform Governance

Engagement Type: Experimental Prototyping · Research-Through-Design · Technical Specification & Architecture

Focus: Agentic and non-deterministic interaction models, interpretability and inspection patterns, human-in-the-loop oversight, system-level UX foundations

Tools: ChatGPT, Figma Make, FigJam, Google Workplace, Dovetail, Zoom, Canva

In a wide-ranging interview, Jack Dorsey reflects on his departure from Bluesky, critiques how traditional social platforms handle moderation and censorship, and argues that centralized social media cannot remain censorship-resistant without moving to open protocols. Dorsey also argues that platforms should separate the underlying protocol from corporate control. I reference this particular interview for its articulation of a protocol-based critique of platform governance, not as an endorsement of the publication's broader editorial stance. Read article

The Problem

Every time someone opens a social media feed, a series of interpretive decisions has already been made:

which posts appear

which are deprioritized

which are flagged as sensitive

which are amplified, limited, or withheld

These decisions shape experience, behavior, and perception. Yet for the person scrolling, the reasoning behind them is almost always invisible.

Over time, this invisibility produces predictable outcomes:

feeds feel arbitrary or manipulative

control tools are blunt and reactive

trust erodes because nothing can be inspected

platforms absorb interpretive responsibility without shared accountability

Most existing transparency efforts focus on policy disclosure or on feedback from enforcement. They explain what happened after the fact, but not how or why meaning was constructed in context.

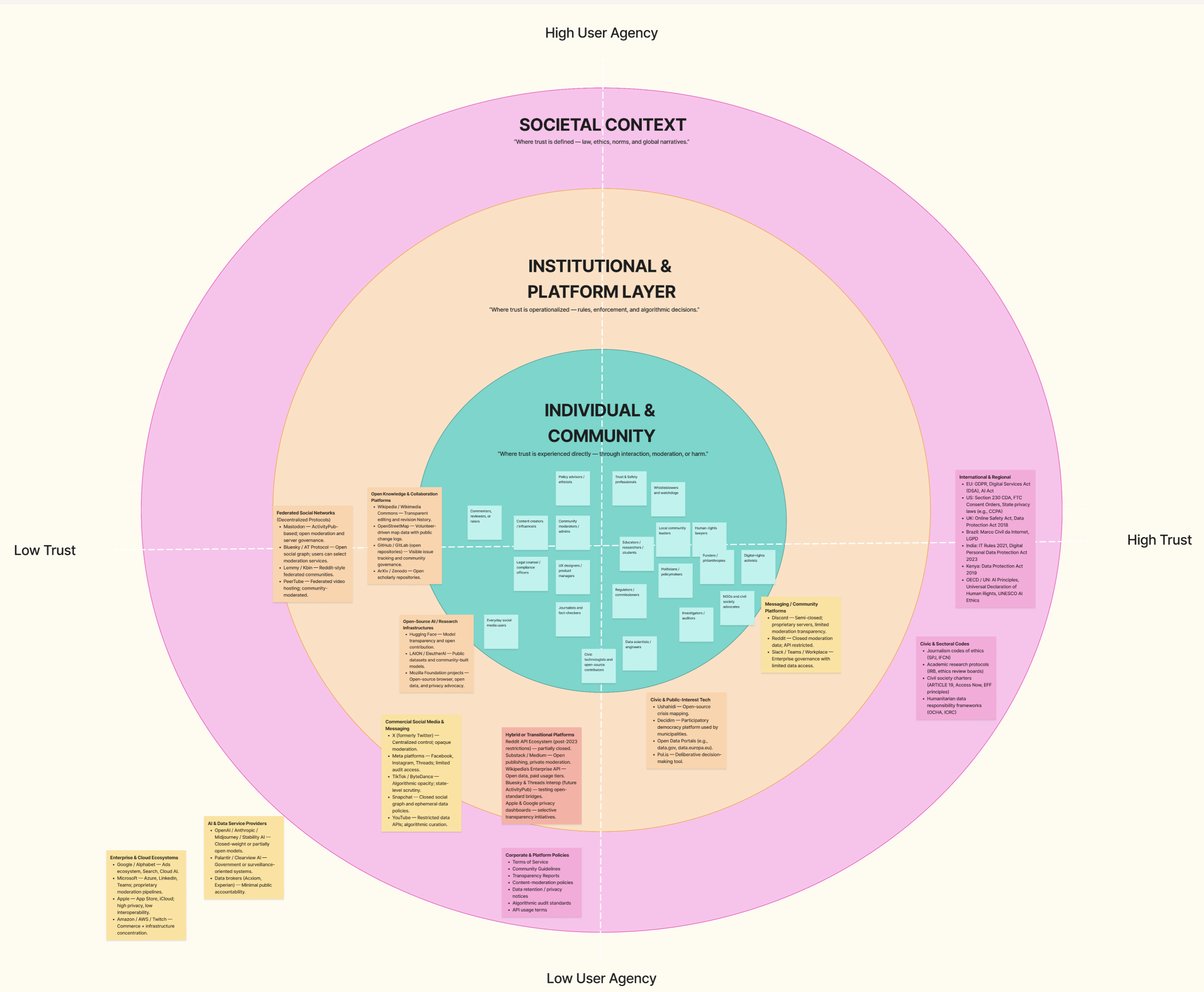

The Social Media Trust Eco-System: A layered model of the social media trust ecosystem, showing how individual and community experiences are shaped by platform governance and broader societal norms, laws, and institutions.

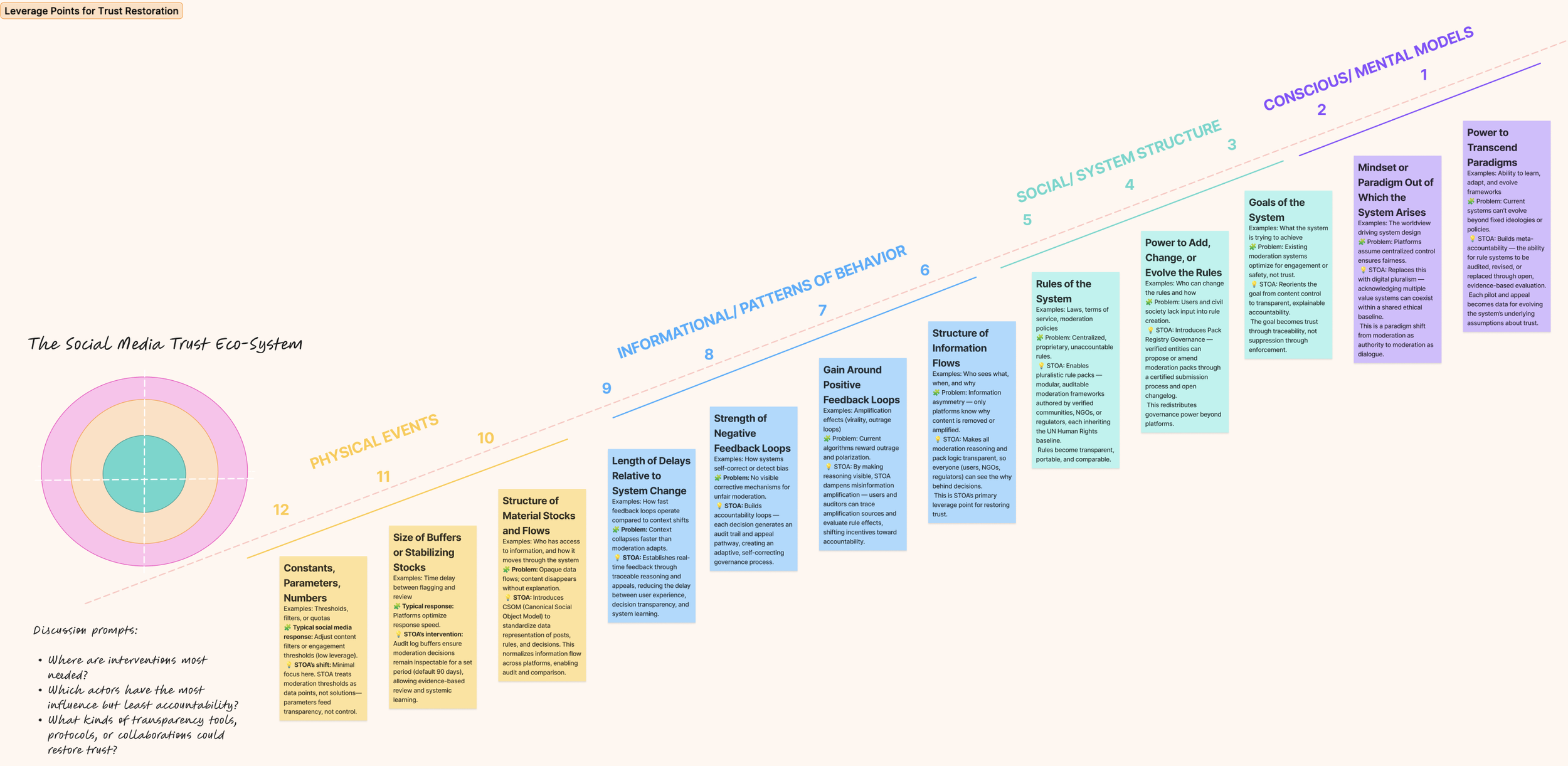

Social Media Systems Leverage Map: A tool for identifying opportunties to restore trust on social platforms, grounded in Meadows' "places to intervene in a system," showing intervention points from feedback loops to governance and paradigms.

Project Goals

I began working in online systems in 2004 as a content producer and community manager, when moderation decisions were made manually, under pressure, and with little structural guidance.

Over the next two decades in UX, service design, and organizational systems, one pattern remained consistent: conflict rarely stems from disagreement over rules, but from opacity—people are affected by decisions they cannot see, question, or understand.

As platforms scaled and automation increased, that opacity deepened. Interpretation became embedded in systems, while accountability remained diffuse.

STOA emerged as a self-directed project to examine this failure mode, free from delivery pressure and institutional constraints. Its aim is not to “fix social media,” but to study one problem in depth: interpretation without visibility.

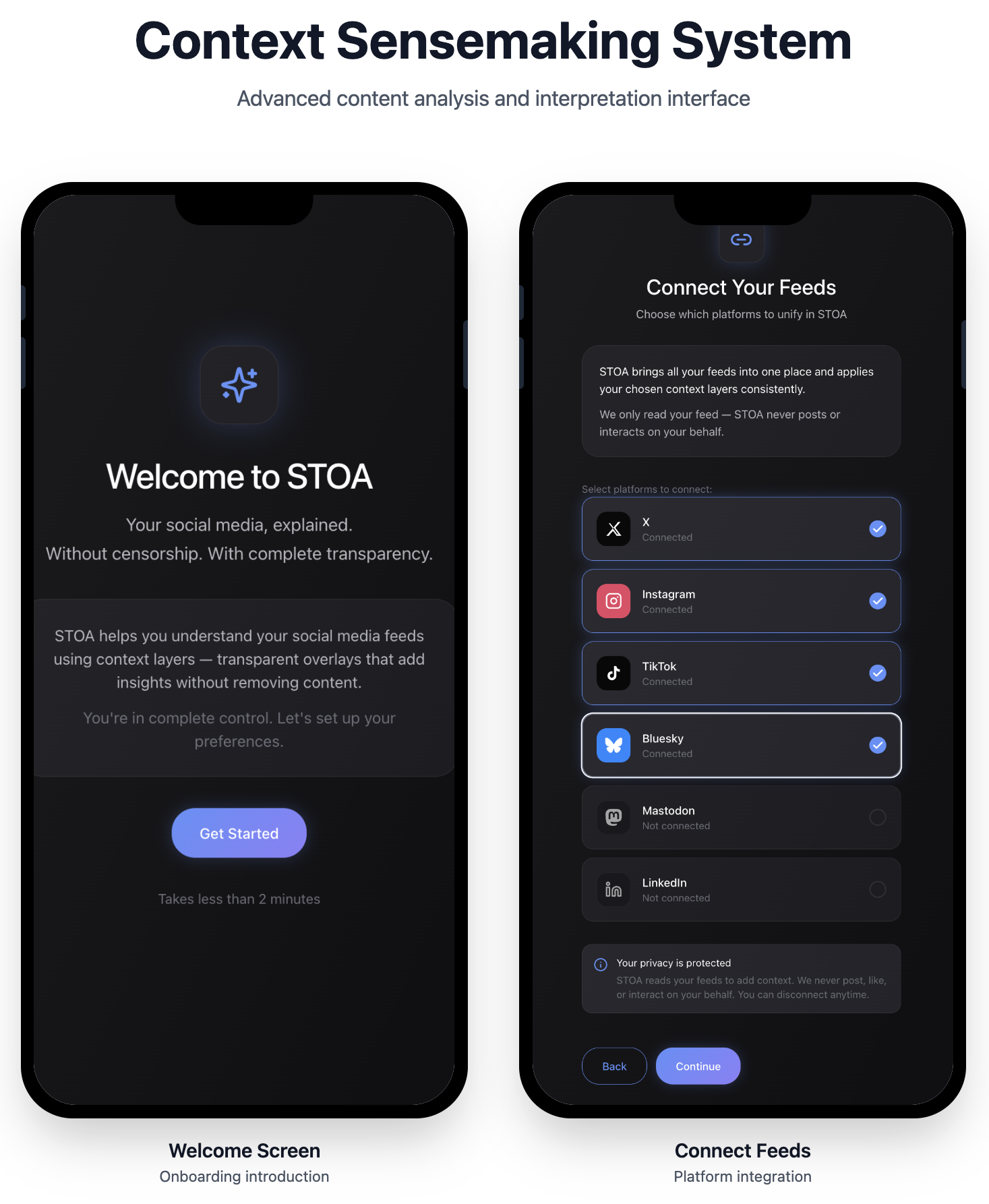

Over roughly 6 months, I created artifacts that enabled me to develop the backend powering STOA and a front-end app to test its capabilities with various subject matter experts. This rights-aligned transparency model uses progressive disclosure to give users control over when and how contextual explanations are revealed while enforcing always-on rights constraints, which is a core function of the user experience.

In developing STOA, I used AI tools (including Figma Make, ChatGPT, and Dovetail) selectively to accelerate early technical exploration—such as drafting pseudocode, testing symbolic logic representations, and stress-testing specification language. All system architecture, reasoning models, constraints, and design decisions were authored and validated by me. AI functioned as a rapid reasoning assistant, not a decision-maker, allowing me to iterate faster while maintaining full interpretive and ethical control.

A design science approach.

STOA was conducted as a design science and research-through-design project.

Rather than starting with features or requirements, the work began by observing:

where interpretation occurs

where ambiguity produces friction

where users lose agency

where systems obscure their own reasoning

Key methodological characteristics:

No predefined feature list

No traditional requirements gathering

Research used as constraint, not validation

Artifacts treated as hypotheses about system behavior

Technical schemas, reasoning structures, and interaction patterns were iteratively refined as probes into how interpretive systems might behave differently if transparency were built into the system rather than retrofitted.

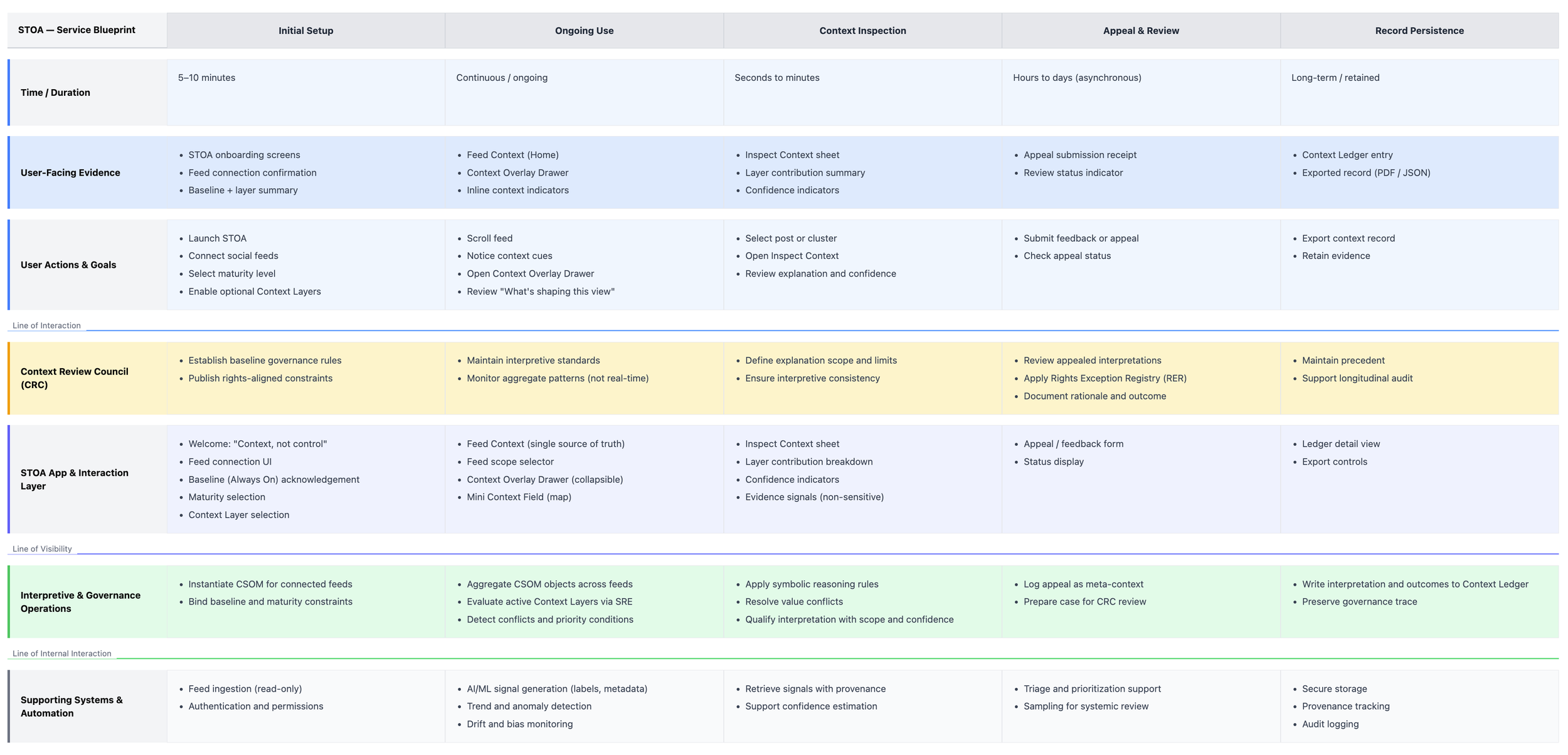

End-to-end service blueprint for STOA, mapping user actions, interface layers, human governance (CRC), and supporting systems across onboarding, everyday use, inspection, appeal, and long-term record keeping.

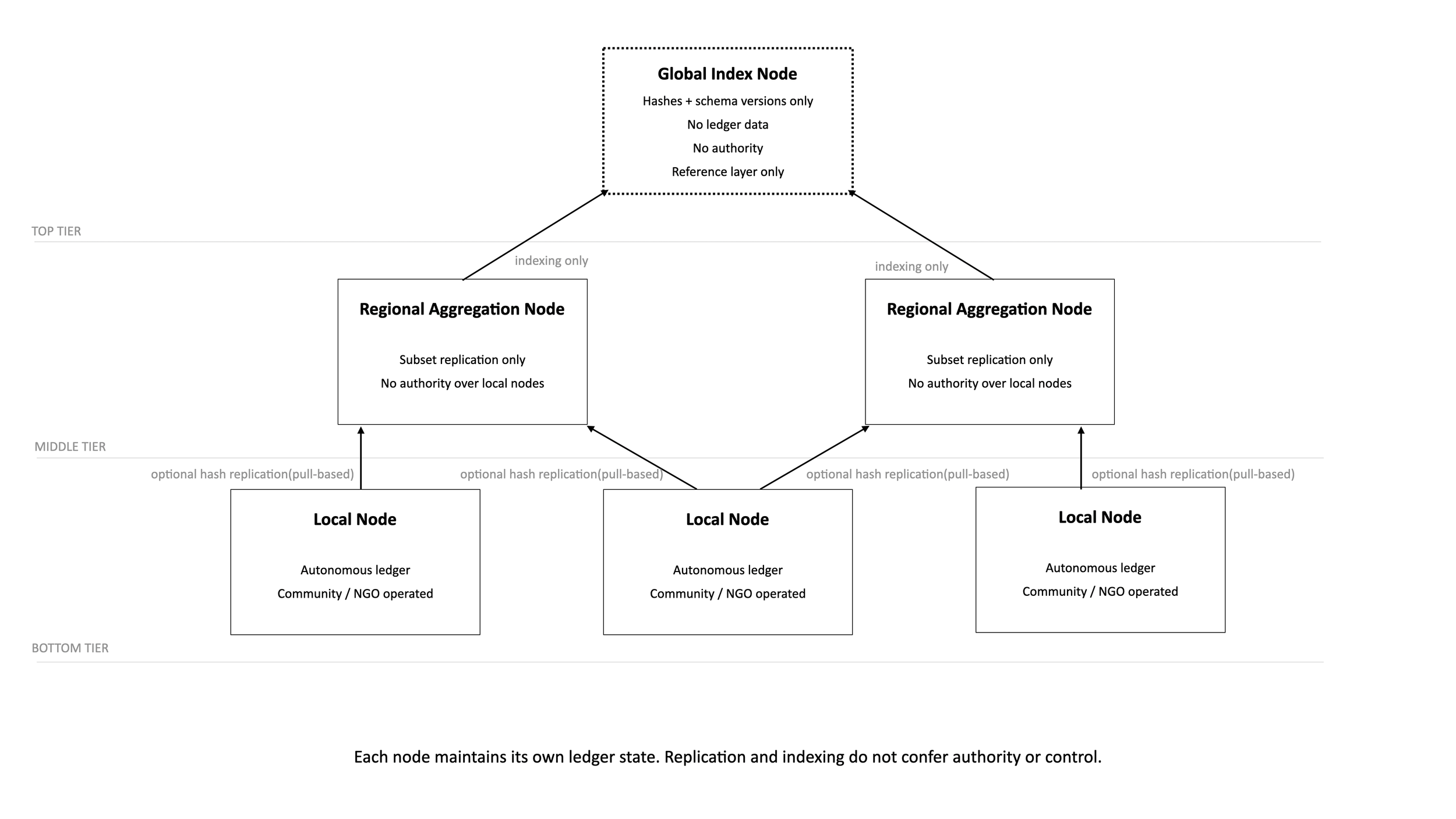

STOA consists of two interdependent components:

A protocol-level technical architecture that defines how interpretation is represented, reasoned about, and recorded

A reference application (STOA App) that demonstrates how those interpretations can be made usable

Both were designed together to ensure that the explanation would be a first-class system output, not an afterthought.

What I designed:

The Interpretive Core: Making Social Meaning Legible and Governable

At the center of STOA is the Interpretive Core, a deliberately designed pairing of two elements:

Canonical Social Object Model (CSOM), stabilizes what is being interpreted

Symbolic Reasoning Engine (SRE), makes explicit how interpretation occurs

Together, these components allow social media systems to represent meaning, apply ethical constraints, and generate explanations that are inspectable, contestable, and user-facing.

The Interpretive Core exists to address a structural failure common to social platforms:

Systems constantly make interpretive decisions, but neither the objects being interpreted nor the reasoning applied to them are defined in ways that can be explained, reviewed, or governed.

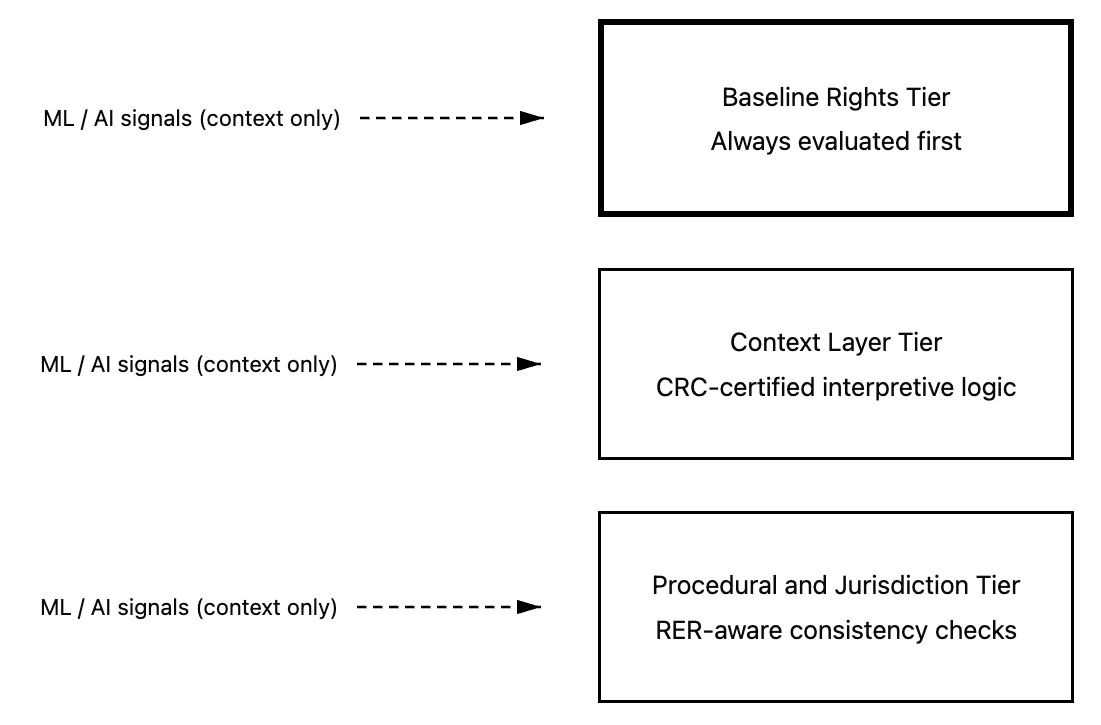

AI as Operational Infrastructure, Not Interpretive Authority

STOA is designed for large-scale digital environments where AI and machine learning systems are unavoidable for handling volume, velocity, and diversity of content.

At a global scale, AI is required to:

generate content-understanding signals across languages and media types

support triage, prioritization, and anomaly detection

monitor drift, bias, and systemic failure patterns

enable safety and non-exposure guarantees reliably

STOA does not treat AI outputs as decisions or truth.

Instead, AI-generated outputs are treated as fallible, probabilistic signals.

The protocol's core contribution is to define how those signals are represented, constrained, reasoned about, and explained.

The STOA app prototype provides a controlled sense-making environment that uses synthetic social data and contextual cues—without live platform access—to study how transparency, explanation, and agency shape user trust and decision-making.

Within STOA:

AI/ML systems generate signals

CSOM standardizes those signals with provenance and confidence

SRE determines how—and whether—those signals are applied under explicit rules, priorities, and exceptions

the Context Ledger records the reasoning path for audit and review

This separation allows automation to scale without collapsing accountability.

AI functions as operational infrastructure, not interpretive authority.

Interpretive decisions cannot be explained if the objects under interpretation are inconsistently defined.

In most social platforms, content is represented differently depending on:

product surface (feed, story, short video, advertisement)

distribution mechanism (organic, boosted, recommended)

moderation state (flagged, restricted, removed)

jurisdictional or policy context

These representations are optimized for delivery and enforcement—not for explanation.

The Canonical Social Object Model (CSOM) establishes a single, platform-independent representation of a social object that includes:

the content itself (text, media, references)

core metadata (source, time, relationships)

distribution context (how and where it appeared)

interpretive signals (sensitivity, amplification, sponsorship)

applicable constraints (jurisdictional, age-based, rights-related)

CSOM does not encode platform policy or enforcement outcomes.

It encodes the conditions under which interpretation occurs.

By stabilizing how social content is represented, CSOM makes interpretation:

comparable across contexts

decoupled from platform implementation

stable enough to support explanation, review, and audit

Without CSOM, transparency collapses into ad hoc, surface-level descriptions tied to specific interfaces rather than to meaning.

Canonical Social Object Model (CSOM)

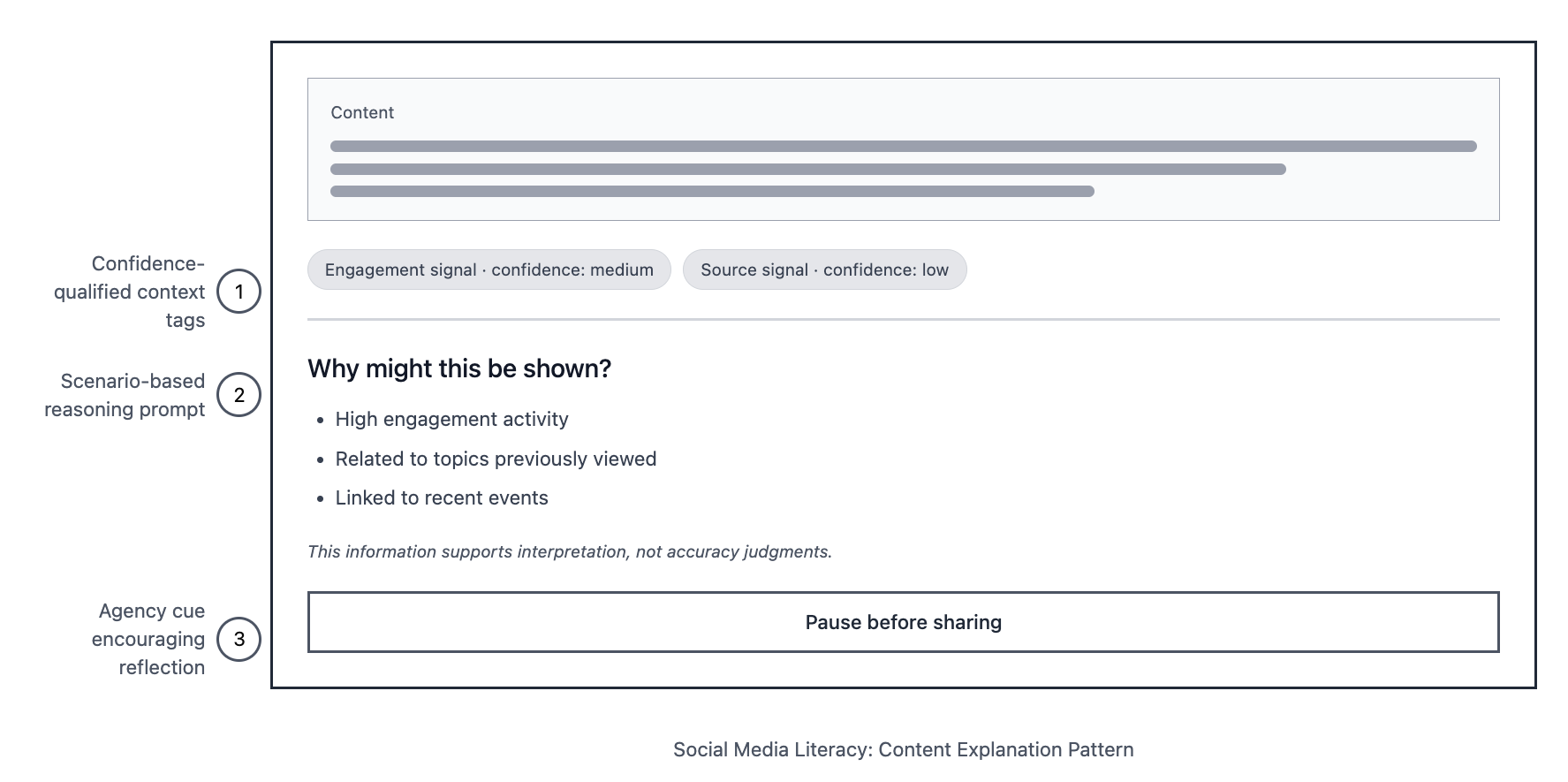

An example of a content explanation pattern that makes recommendation signals visible, qualifies confidence, and prompts reflection—supporting interpretation and user agency rather than judgment or enforcement.

Symbolic Reasoning Engine (SRE)

Where CSOM defines what is being interpreted, the Symbolic Reasoning Engine (SRE) defines how interpretation happens.

The SRE is a rule-based system grounded in symbolic logic, designed to make ethical and governance principles executable rather than declarative.

It is not a machine learning model.

It does not optimize predictions or produce probabilistic judgments.

Instead, it explicitly represents:

values and principles

constraints and obligations

priorities and exceptions

uncertainty and scope

This reflects a core design assumption: ethical reasoning depends on explicit rules, conditional logic, and traceable justification, rather than on statistical inference.

The Interpretive Core transforms canonical representations into structured reasoning outputs.

Inputs include:

CSOM representations of social objects

contextual signals (e.g., jurisdiction, age context, declared preferences)

rights-based and safety constraints

governance structures (exceptions, review requirements)

How the Interpretive Core Functions

The reasoning process involves:

applying symbolic rules to canonical objects

resolving conflicts between principles

qualifying interpretations with scope and confidence

recording provenance and decision paths

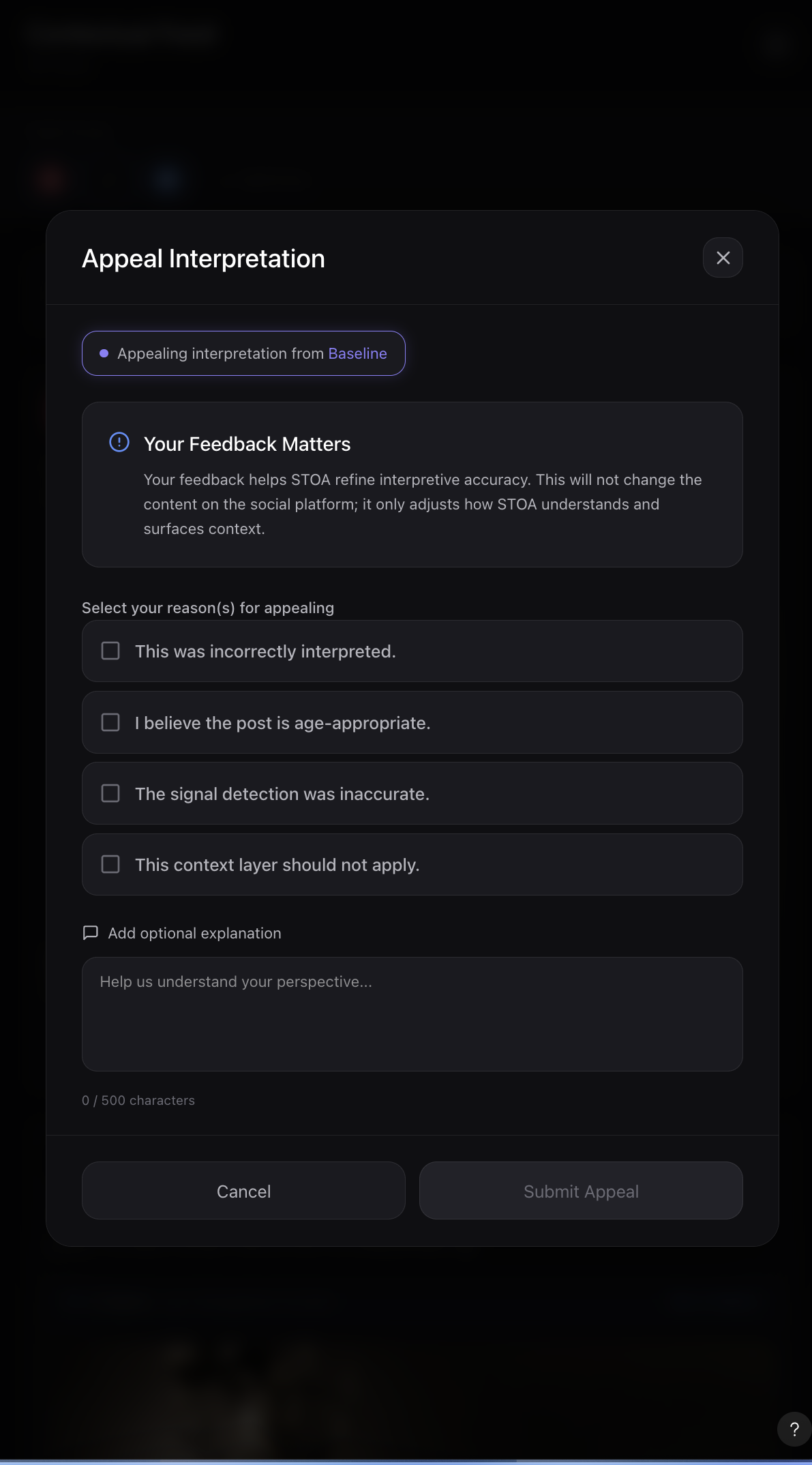

Outputs are not enforcement actions, but interpretive explanations designed to be surfaced to users, auditors, or reviewers.

This separation ensures that:

interpretation does not automatically trigger control

reasoning can be inspected without coercion

disagreement is possible without system failure

The federated STOA architecture shows how autonomous local ledgers can be indexed and aggregated across regions without transferring authority or control.

Ethics as System Logic

Rather than expressing ethics as abstract policy statements, STOA encodes ethical principles as:

constraints (e.g., non-exposure to harmful material)

obligations (e.g., surface context when confidence is low)

priorities (e.g., rights-based exceptions override preference-based filters)

Ethics, therefore, shape system behavior directly and consistently over time.

Conflict, Priority, and Accountability

Real-world governance involves disagreement.

The Interpretive Core is explicitly designed to:

surface when principles collide

show which rule took precedence

document when exceptions were applied

Rather than hiding complexity, the system makes value conflicts visible in bounded, reviewable ways.

Research & Subject-Matter Expert Engagement

Secondary Research

The project draws on peer-reviewed research in:

platform governance

transparency and procedural justice

algorithmic accountability

media literacy

This research shaped constraints on what the system should not do as much as what it could do.

Interviews & Co-Design Workshops

I conducted interviews and participatory design sessions with subject-matter experts across:

digital rights

AI ethics and safety

journalism

civic technology

human–computer interaction

Rather than soliciting requirements, sessions were structured to surface:

reasoning breakdowns

ambiguity points

safety risks

governance constraints

Many design decisions emerged from where experts struggled to explain existing systems, not from explicit prescriptions.

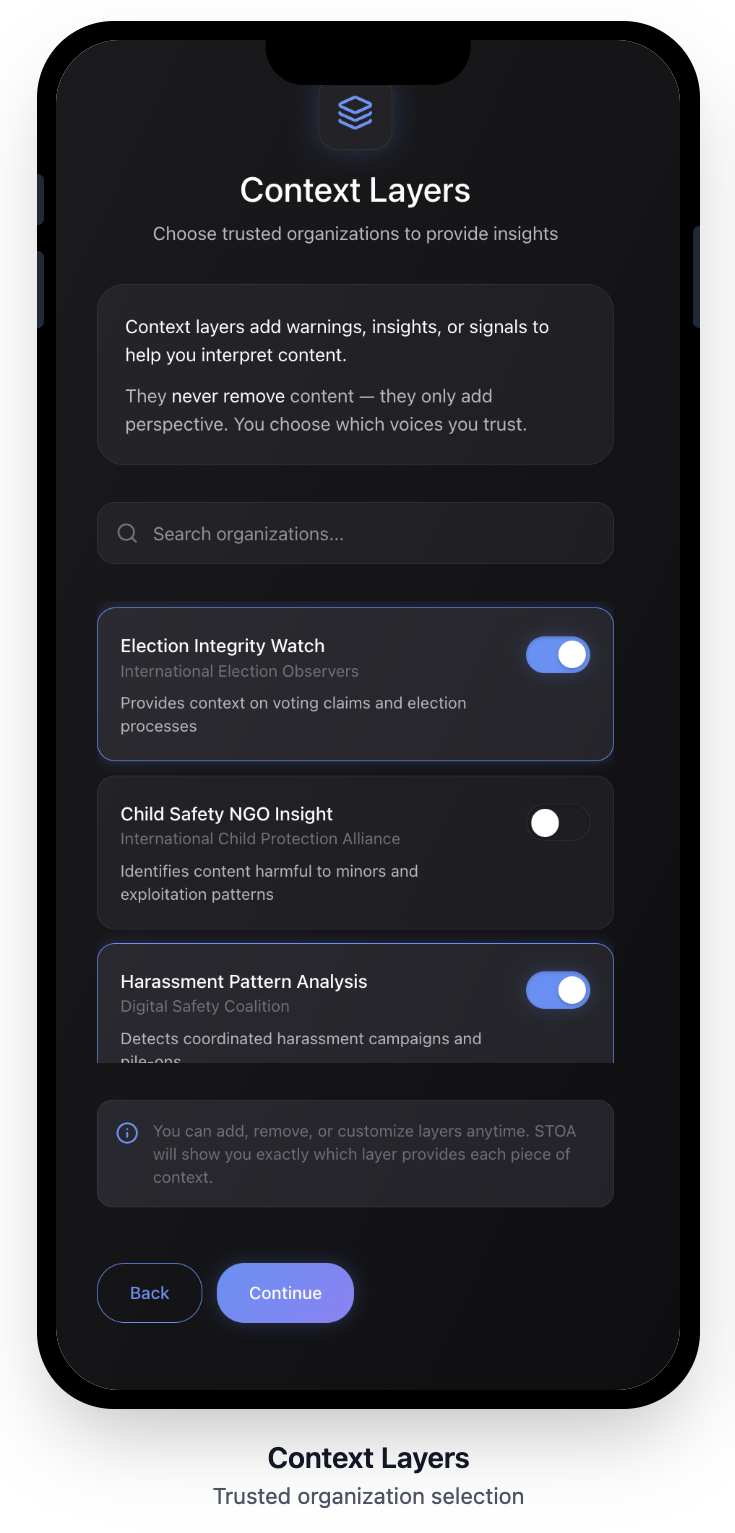

Context Layers

Context layer selection in STOA, where users choose trusted organizations to add explainable signals and insights to their feed—without removing content or limiting expression.

Context Layers represent different interpretive perspectives—such as safety, relevance, amplification, or sponsorship—that can be examined independently.

A key design decision was to separate interpretation from enforcement, allowing meaning to be surfaced without immediately triggering control actions.

Impact

STOA is a design science case study demonstrating how transparency, ethics, and agency can be designed directly into the structure of social media systems—even at a global scale.

It reflects how I work when problems are ambiguous, systemic, and consequential—and when the goal is not to ship a feature, but to change how a system can be understood.

Public Artifacts

Technical Specification (Preprint)

https://zenodo.org/records/18154981

Share STOA App Feedback

What's Next

Peer-reviewed publication

Continued feedback on the technical specification

Usability and interpretability testing of the STOA App

Planned presentations:

Peer-reviewed paper ‘STOA: A Rights-Aligned Interaction Model for Transparent Digital Governance Through User-Governed Context Layers’ published by HCI International

HCI International Conference — Summer 2026